Maria Ramos

Maria Violet is a writer interested in comic books, cycling, and horror films. Her hobbies include cooking, doodling, and finding local shops around the city. She currently lives in Chicago with her two pet turtles, Franklin and Roy..

Home invasion movies are an old and popular genre in horror, and it is possibly the only horror genre that is targeted more towards women. This may be because in the real world, women are taught to fear strangers and the dangers they represent on a greater scale than men. The home has also historically been portrayed as a woman’s place, one of the few in which a woman was expected to take charge. In a society where men are viewed as the physical protectors of the home, having a solitary woman pursued and under attack by an ill-intentioned invader is a popular narrative tool used to inspire terror.

Home invasion movies are an old and popular genre in horror, and it is possibly the only horror genre that is targeted more towards women. This may be because in the real world, women are taught to fear strangers and the dangers they represent on a greater scale than men. The home has also historically been portrayed as a woman’s place, one of the few in which a woman was expected to take charge. In a society where men are viewed as the physical protectors of the home, having a solitary woman pursued and under attack by an ill-intentioned invader is a popular narrative tool used to inspire terror.

The problem this presents is that it implies women without men are more vulnerable and less able to defend themselves. It also often places men in a predatory role. This involves a certain amount of sexism in both directions, indicating a woman’s weakness and a man’s supposedly aggressive nature. These movies tend to show women as terrified and helpless, being stalked by the big bad wolf in the form of an unknown assailant. Both an outdated stereotype and a harmful one, this sub-genre of horror can have real world negative effects as it reinforces insulting ideas about women’s strength. Even when the woman escapes, the implication remains that they survived against the odds rather than as a matter of course.

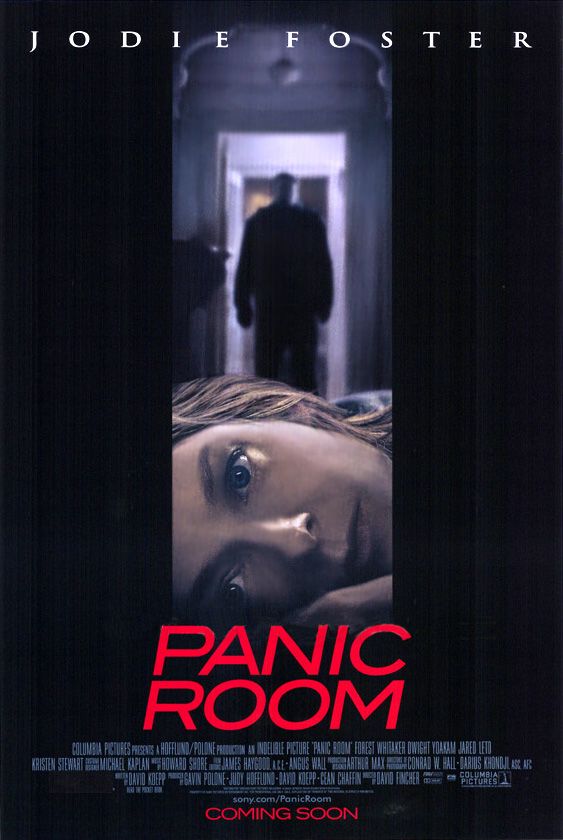

For example, in Panic Room (2002) the female protagonist feared danger so greatly that she literally hides in a panic room with her sick child (not a feature that most homes contain), though ironically a working cell phone was not something she thought to store there.

For example, in Panic Room (2002) the female protagonist feared danger so greatly that she literally hides in a panic room with her sick child (not a feature that most homes contain), though ironically a working cell phone was not something she thought to store there.

Her eventual bid to escape is not due to inherent bravery, but in order to get treatment for her daughter. In Funny Games (1997), both a husband and wife are attacked, but the implication exists that it is the man’s job to fend off the attackers while the women, his wife, is only expected to escape at best. Instead, they both die. In The Strangers (2008), a more modern film, a similar setup occurs through one of the three assailants is actually a woman. The female half of the attacked duo in this case survives, satisfying the “final girl” trope popular in all genres of horror.

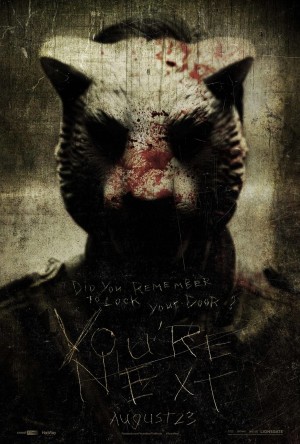

Though this final girl trope of having one surviving woman at the end of a horror film tends to play out more often in scenarios where there are groups under attack, such as slasher films, there are examples found in the home invasion category as well. The film You’re Next (2013) is another such example, where Erin is the last woman standing after killing four attackers and then, accidentally, one police officer. She survives but is on the hook for the deaths even though they were in self-defense or accidental. This movie is a bit of an exception in the genre in general anyway, due to Erin’s ability to physically fight back.

In fact, often women in these movies use their wits rather than their strength to fend off attackers. Wait Until Dark (1967) stars Audrey Hepburn as a woman being terrorized by three men searching for drugs in her home. To emphasize her vulnerability even further she is blind in the film, but there the convention is turned on its head. Hepburn’s character uses her blindness as an advantage, plunging the robbers into the dark and setting traps they cannot see to avoid. She likely would have had an easier time had this movie been set more recently, as a security system would have done her job for her.

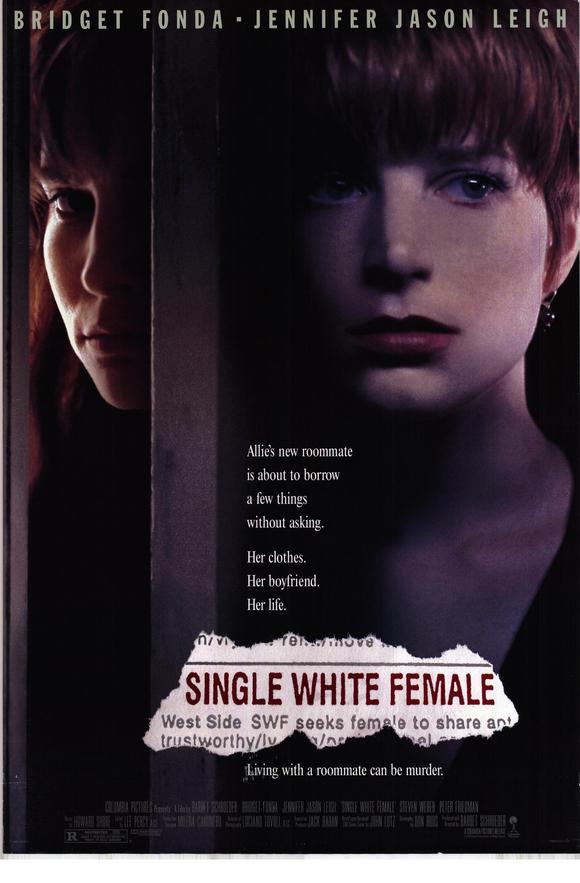

Women are sometimes the attackers as well. 1992’s Single White Female is a perfect example. Hedy is the murderous assailant – though that is not apparent at first – and she manages to kill two men and severely injure a third in her pursuit of Ally, the “victim.” In the end, Ally is able to outwit her, once again relying on the positive brains over brawn narrative. Though the women here are not portrayed as weak in the same way as other movies in this genre, there are nevertheless negative stereotypes at play. One is of women as constantly being in competition with and jealous of each other. After all, there is no better way of portraying jealousy than literally trying to take over someone’s life. Another is of the crazy or unstable woman, an extremely damaging stereotype of its own. Those same stereotypes are at play in 2007’s Inside, where a woman stalks and eventually kills a mother-to-be in order to claim her child as her own.

Women are sometimes the attackers as well. 1992’s Single White Female is a perfect example. Hedy is the murderous assailant – though that is not apparent at first – and she manages to kill two men and severely injure a third in her pursuit of Ally, the “victim.” In the end, Ally is able to outwit her, once again relying on the positive brains over brawn narrative. Though the women here are not portrayed as weak in the same way as other movies in this genre, there are nevertheless negative stereotypes at play. One is of women as constantly being in competition with and jealous of each other. After all, there is no better way of portraying jealousy than literally trying to take over someone’s life. Another is of the crazy or unstable woman, an extremely damaging stereotype of its own. Those same stereotypes are at play in 2007’s Inside, where a woman stalks and eventually kills a mother-to-be in order to claim her child as her own.

In all these films, the sanctity of the home – an historically female sphere – is disturbed and a woman is shown as the main or ultimate victim. Most show women being forced to rely on their cleverness to protect them rather than a direct physical defense. The home becomes a trap that must be escaped, in fact an apt allegory for repressive sexism in general.

However, there are differences as well, and signs of change in more recent movies. This genre sometimes has a woman as the attacker as well as the victim. There is even the occasional physical battle in which the woman triumphs. This is a sign of progress both in fiction and hopefully in how women are viewed in real life. Though the genre has historically relied on incorrect and offensive stereotypes of the weak and frightened female victims, if it continues to show women in the stronger role of successful defender and even sometimes attacker, the genre may be able to successfully evolve with the times.

What YA dystopian fiction doesn’t portray…

What YA dystopian fiction doesn’t portray… While traditional dystopian fiction wouldn’t seem to appeal to the young adult demographic, many of the currently popular works, such as

While traditional dystopian fiction wouldn’t seem to appeal to the young adult demographic, many of the currently popular works, such as  Further, while these novels and films are offering up more in the way of female protagonists, the girls in question more often than not succeed due to their ability to act more like their male counterparts rather than less. They compete on the same level and without any mention of historical inequalities that have beleaguered them i.e. their assumed inferiority, or their being supposedly

Further, while these novels and films are offering up more in the way of female protagonists, the girls in question more often than not succeed due to their ability to act more like their male counterparts rather than less. They compete on the same level and without any mention of historical inequalities that have beleaguered them i.e. their assumed inferiority, or their being supposedly