Alayna Cole

Alayna Cole is an MCA (Creative Writing) candidate who loves to write stories when she’s not studying.

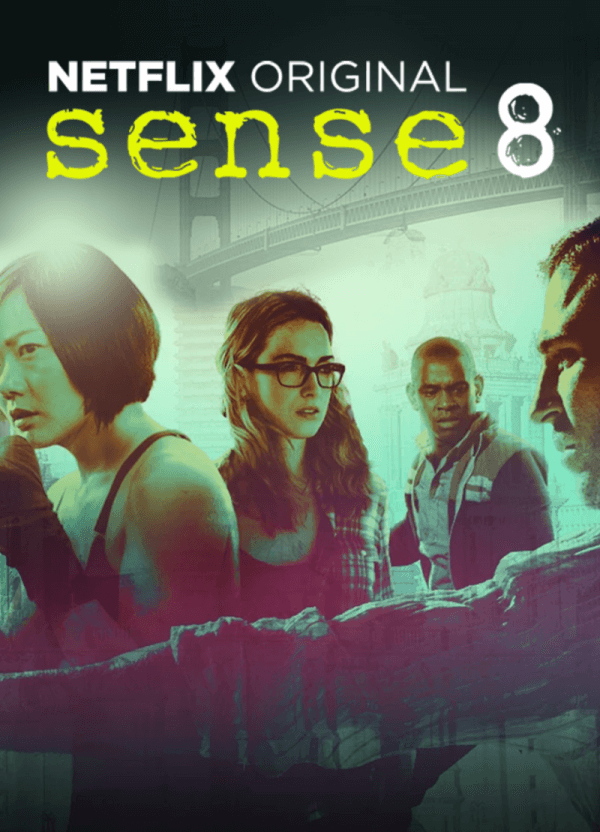

It’s probably the writer in me talking when I say that I’m a sucker for interesting narrative choices and meaningful characterisation, and Sense8 delivers these things in veritable bucket loads. The 12-episode first season takes advantage of its Netflix-supported platform to deliver a visceral, complex, and intelligent experience that I devoured in one sitting.

It’s probably the writer in me talking when I say that I’m a sucker for interesting narrative choices and meaningful characterisation, and Sense8 delivers these things in veritable bucket loads. The 12-episode first season takes advantage of its Netflix-supported platform to deliver a visceral, complex, and intelligent experience that I devoured in one sitting.

The show follows the individual stories of eight ‘sensates’ from eight cities with very different life experiences and abilities; these eight characters form a ‘cluster’ who become psychically attuned to tap into one another’s thoughts, senses, and memories as the season progresses. The empathy these characters develop in their deep understanding of one another is extended to the audience, as we feel elated at their successes and devastated by their failures.

Each member of the cluster is able to ‘visit’ the others or ‘share’ one another’s bodies. A sensate that possesses useful skills often takes over another to help them when emotions are running high, particularly in life-threatening situations. The sensates possess a variety of skills—martial arts, weapons knowledge, driving, computer hacking, and chemistry among them—and there is always an audience air-punch moment when you work out who was needed to assist in a particular scene or when things play out as you expected (often with some added awesomeness that you hadn’t even considered). The action sequences in the second half of the season are even more impressive as the sensates start to rack up combo moves, with four or five sensates taking over for different parts of a master plan so that everything runs perfectly.

Air-punching isn’t the only emotional reaction Sense8 provoked in me. I was incredibly angry for Nomi—a hacktivist and transwoman—when her mother disrespected her and her use of preferred pronouns, was gutted by the sad events composing DJ Riley’s history, and cried tears of joy for Mexican actor Lito’s personal journey. Sense8 prioritises the characterisation of individuals over the season plot arc and, while this makes for some clumsy exposition in places, it shines the spotlight sharply on the shared experiences of these eight totally different yet fundamentally human characters.

Being on Netflix, rather than mainstream television, allows Sense8 to accurately, shamelessly—and sometimes quite graphically—depict the human experience, connecting to the show’s central premise of human connection and empathy.

Being on Netflix, rather than mainstream television, allows Sense8 to accurately, shamelessly—and sometimes quite graphically—depict the human experience, connecting to the show’s central premise of human connection and empathy.

Sense8 refuses to shy away from topics and images that are generally considered taboo: sexuality and gender diversity, racial diversity, religion, sexual and non-sexual nudity (including incredibly symbolic scenes of babies crowning) and graphic violence. When criminal safe-cracker Wolfgang accidentally visits conservative chemist Kala while he was swimming naked at a bathhouse, his stark, non-sexual nudity reminded me of just how ‘human’ this show is. The openness with which Sense8 includes and explores the primal, natural aspects of the human experience reinforces its attempt to induce empathy.

The empathy fostered by Sense8 also makes it perfect for exploring diversity, and the show certainly makes use of this platform. Of the eight main characters, two—Lito and Nomi—are sexually attracted to their own gender and are in loving, dynamic relationships with fantastic secondary characters. Some viewers have considered these queer characters stereotypical or believe that Sense8 spends too much time focusing on their sexuality rather than other aspects of their characters, but I disagree; while the characters are used as vehicles to explore queer issues—including the journey from shame to pride, reaching self-acceptance, overcoming bullying and oppression, and the impact sexuality can have on families or careers—queer relationships are not given more attention than those relationships that are more commonly seen in the media. I assume that most criticisms about the amount of queer representation and discussion in Sense8 are founded in perception bias, with audiences not used to being exposed to such diversity.

Not only does the show seek to expose audiences to varied sexualities and genders, but it also provides an employment opportunity for gender-diverse actors and actresses to fill these roles. Jamie Clayton, who portrays Nomi, is a transwoman, and her own experiences give Nomi’s story incredible weight and significance.

These behind-the-scenes choices continue to impress. Actors hired for the cast aren’t all from Hollywood, with many having successful careers in Korea or India or Africa, where their characters live. Everything is shot on location—explaining Sense8’s high budget—and extras are sourced domestically, which further contributes to the feeling of authentic diversity that the show produces.

These behind-the-scenes choices continue to impress. Actors hired for the cast aren’t all from Hollywood, with many having successful careers in Korea or India or Africa, where their characters live. Everything is shot on location—explaining Sense8’s high budget—and extras are sourced domestically, which further contributes to the feeling of authentic diversity that the show produces.

Though a mix of cultures is represented, the characters don’t seem token. For example, there are a wide variety of Indian characters in the show, some religious, some not, some living in India, others having moved elsewhere at a young age, some always in traditional dress, others not, some in arranged marriages, others pursuing love marriages. Kala’s storyline focuses on the difficulty of making decisions for love while navigating family pressures.

There are many other points where the diversity of characters is explored, but also where their underlying similarities are emphasised: each of the eight sensates in the cluster are strong, but in different ways; they have very different families, but most have lost a parent or parental figure; and they experience strange psychic phenomena, but react differently based on their cultural context and personality. It’s been suggested that this diversity might be off-putting for some critics, but for many viewers (myself included) it’s inspiring.

Even with the occasional confusing or neglected plot point, the first season of Sense8 is incredibly intelligent and gives me high hopes for future seasons. There is extensive use of symbolism to add to the already important characterisation of the sensates and secondary characters. In particular, the childbirth scene mentioned earlier depicts each sensate’s first breath: Wolfgang’s water birth reflects his time in the bathhouse, Lito’s birth in front of a television is indicative of his acting career, and Nomi’s c-section places further symbolic distance between her and her mother. The many settings in the show are symbols too, with Woflgang’s Berlin a dark, rainy depiction that reflects how he sees his life, sitting in stark contrast to the bright and colourful San Francisco where Nomi lives. The cuts between characters feeling similar emotions in slums and expensive apartments, prisons and art galleries, further emphasises the external differences but inner similarities of the sensates, and all people.

Sense8 is a slow burn, with some ambiguity in the first few episodes to reflect the confusion of the sensates, and this could be a turn-off for some, but with shows like Game of Thrones (the ultimate slow burn!) at the pinnacle of popularity, many will be able to excuse this. The intelligence of the show encourages the audience to think, rather than simply consume, and to theorise about what might happen next.

I can’t stop thinking about the links between Kala working for a company that creates pharmaceuticals; Korean businesswoman Sun and her father’s involvement in the pharmaceutical industry; African bus-driver Capheus and his desire to buy pharmaceuticals to help his mother live with AIDS; and the impact drugs have had on Riley’s storyline. Surely lines will be drawn between these similarities in the next season’s plot arc?

Sense8 is laced with so many tiny, intricate details that I’m sure there are many more interesting connections that I’m yet to notice and explore. While I’m waiting with bated breath to hear if Netflix will renew the show for season two, I know I won’t be able to resist re-watching these twelve episodes in search of more.

I’m a writer who primarily concerns herself with the page. I’ve found that there are many benefits to favouring written narrative over alternatives like visual and interactive narrative, but there are also many downsides. And, beyond that, there are innumerable differences that cannot necessarily be put into ‘pro’ or ‘con’ categories. This article concerns itself with one of the key differences between my preferred craft and the visual narrative, specifically live action movies and television programmes.

I’m a writer who primarily concerns herself with the page. I’ve found that there are many benefits to favouring written narrative over alternatives like visual and interactive narrative, but there are also many downsides. And, beyond that, there are innumerable differences that cannot necessarily be put into ‘pro’ or ‘con’ categories. This article concerns itself with one of the key differences between my preferred craft and the visual narrative, specifically live action movies and television programmes.

Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a masterful work of speculative fiction, which recollects an unnamed narrator’s childhood, which he is reminded of upon visiting a property known as the Hempstock Farm.

Neil Gaiman’s The Ocean at the End of the Lane is a masterful work of speculative fiction, which recollects an unnamed narrator’s childhood, which he is reminded of upon visiting a property known as the Hempstock Farm.